Reciprocal Coaching: A collaborative and teacher-driven approach to instructional improvement

The Reciprocal Coaching Program, designed by the ConnectED Math team, supports math teachers in improving their practice through peer observation, collaborative reflection, personalized goal-setting, and data-informed decision-making. The program puts teachers in the driver’s seat of their own professional growth by supporting them to set individual goals for their own instructional practice, and then pairing them up as partners to observe each other, analyze data together, and reflect on their instructional choices. Teachers in the program receive feedback and ideas from their coaching partner, and are supported by an intentionally sequenced and facilitated learning progression for teachers.

In order to ground math teachers’ reflections in the reality of student learning and student experience, ConnectED reached out to WestEd to help identify a set of targeted data-gathering tools that teachers could choose from, based on where they were in the coaching cycle. This blog shares how practical measures were integrated into the Reciprocal Coaching program for the 2024-25 school year, what was learned, and how student voice helped sharpen teacher learning.

Why practical measures were a natural fit for Reciprocal Coaching

During the initial pilot of Reciprocal Coaching in the Spring of 2024, we (the Math team at ConnectED) noticed a key gap: math teachers were making thoughtful instructional shifts, but often without insight into how students were experiencing those changes. The traditional assessments teachers were using showed some of what students knew—but not how they felt, collaborated, or engaged with the content. Additionally, teachers asked us for more guidance in selecting teaching actions to try as part of their work in the program, and more support with setting appropriate individual goals.

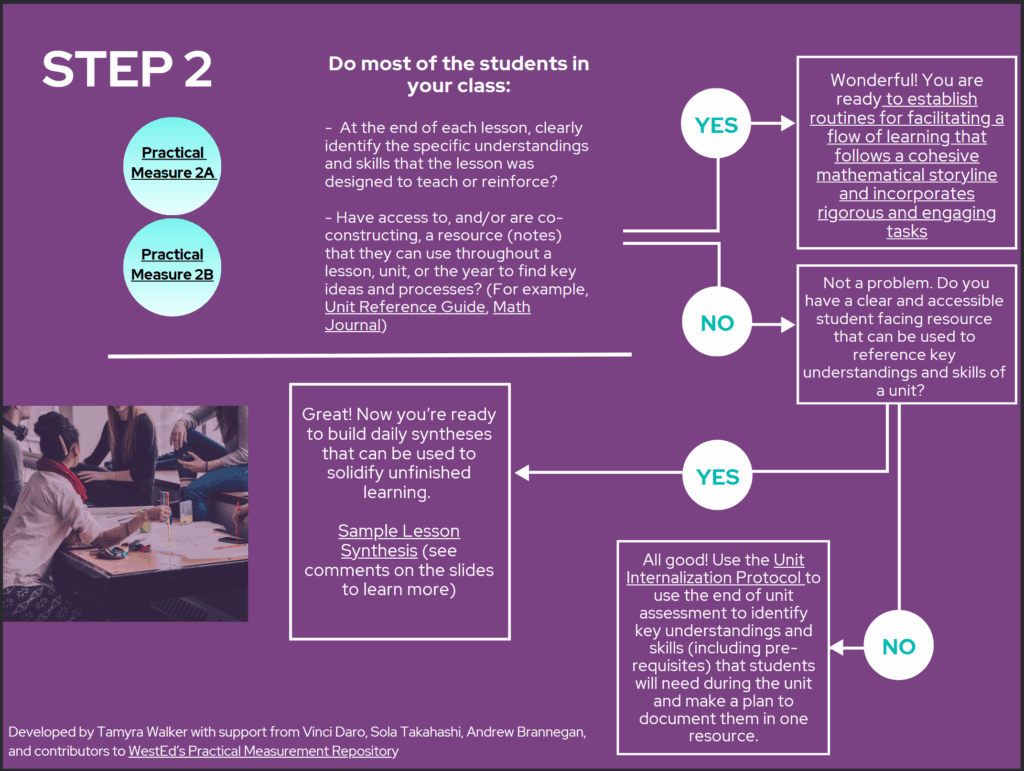

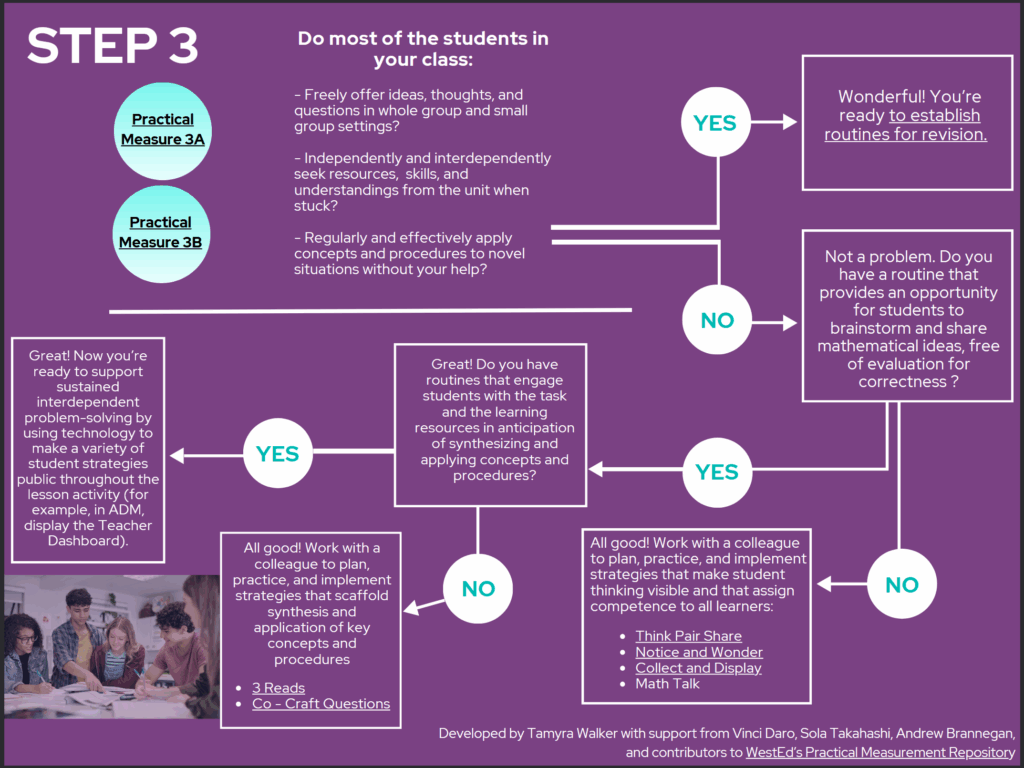

In response to these requests from teachers, we developed three tools: a Decision Tree, which is a step-by-step goal-setting and instructional planning guide, initially designed by Tamyra Walker; a set of short Observation Tools that are aligned to the Decision Tree; and a Planning & Progress Record for coaching pairs to track their work together. We then began exploring the Math Practical Measurement repository, curated by WestEd, to identify and align data collection tools to each step of the Decision Tree; we were looking for short student surveys to integrate into the program that would provide contemporaneous feedback relevant to where teachers were in the Decision Tree. The visual below shows one panel of the Decision Tree, with two practical measures for teachers to choose from at this step in the process.

Practical measures fill a critical gap in instructional coaching programs: they give teachers timely insight into student experience of the content, collaboration with peers, and learning conditions. These tools help teachers connect their instructional decision-making to what students are actually experiencing, not just what is being taught. For many, using practical measures prompts richer reflection and more targeted instructional decisions.

One of our main goals in the Reciprocal Coaching program was to give teachers greater access to the reality of what is happening in their classrooms by incorporating the perspective of a colleague as a kind of mirror to reflect back to each teacher what they might not perceive as easily on their own. The student surveys in the practical measures repository held promise as another kind of mirror, reflecting back the reality of student experience as reported by students themselves. Our hypothesis (and hope) was that embedding the right student surveys, at the right time, within the goal-setting and strategy-selecting process defined by the Decision Tree, would facilitate meaningful use of data from students.

Co-designing and integrating the surveys

WestEd engaged in a collaborative process with ConnectED to understand the Reciprocal Coaching model, aiming to pinpoint critical points in the Decision Tree where teachers could benefit most from targeted insights and data, allowing for more informed decision-making in their instructional practices. After identifying these decision points, we worked together to select and customize practical measures that would help inform teacher actions. These measures were tailored to address specific priorities, such as fostering student collaboration, enhancing content learning, and improving mathematical communication. For example:

- In Step 2 of the Decision Tree shown above, when teachers are asked to assess their student’s understanding of a lesson, a short student survey was created that had students summarize and self-assess their level of learning. [adapted from Mills College Exit Poster]

- In Step 3 of the Decision Tree (see visual below), teachers are asked “do most of your students freely offer ideas, thoughts and questions in whole group and small group settings?” Instead of relying on teacher perceptions of student feelings, a student survey was created using items like “Were you comfortable sharing your thinking in today’s whole class discussion?” and “Would it have been okay to share thinking you were unsure about in class today?” [questions adapted from PMR2’s Whole-Class Discussion & Small-Group work surveys]

These practical measures, aligned to each step in the Decision Tree, were intended to help teachers set student-centered instructional goals, and provide quick, real-time feedback to serve as checkpoints for reflection and decision-making.

Piloting and iterating: Adapting measures for real classrooms

As practical measures were embedded into the Reciprocal Coaching process, teachers began piloting them within their coaching pairs. Many early adopters were early elementary teachers working with students in preliterate or early numeracy stages, and wanted to give their students an opportunity to engage with the measures. To make the surveys accessible, these educators creatively adapted the tools for oral administration—reading questions aloud and replacing written rating scales with visual emojis that students could select in digital forms.

While these adaptations would require further validation to confirm empirical reliability, they were immediately valuable in practice and we decided to support the teachers in experimenting with the measures for use in their own classrooms. Teachers used the results to shape their goals and refine their classroom routines, focusing more on student-centered, inclusive teaching strategies.

Throughout this phase, we maintained regular feedback loops that supported the coaching pairs to iterate on how data was collected, interpreted, and applied. Facilitators played a key role in helping teachers make meaning of student feedback, supporting them to align instructional strategies with what students were reporting. This process helped ensure that the data not only informed teacher learning—but became part of it.

“It’s like weekly PD. And it holds me accountable. Before, I was like, ‘ok maybe next week, or next month… or next year,’ but now I’m doing it, I’m actually doing the things.” —Participating High School Teacher

Uptake by teachers

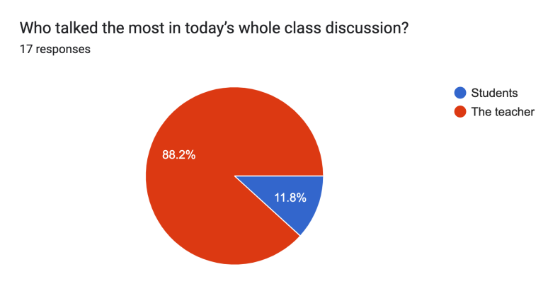

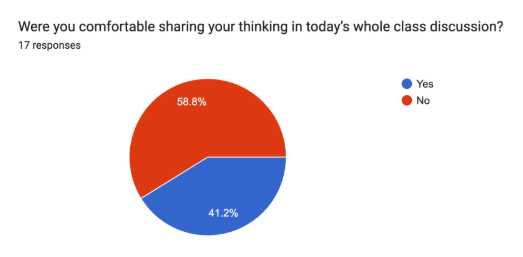

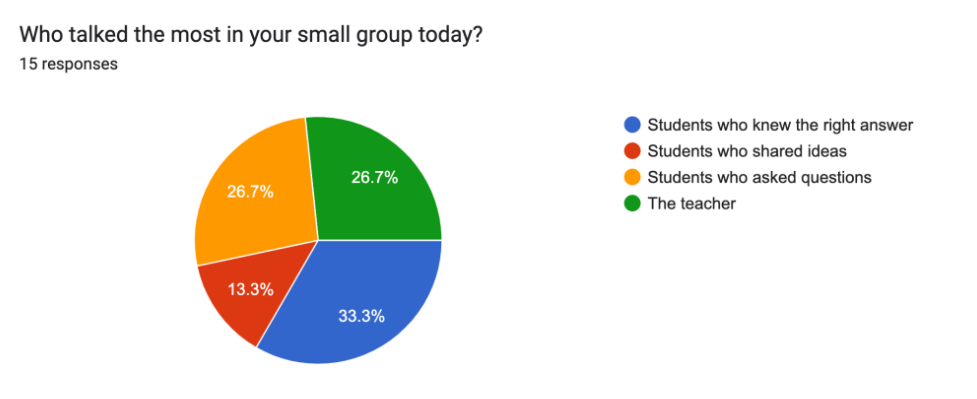

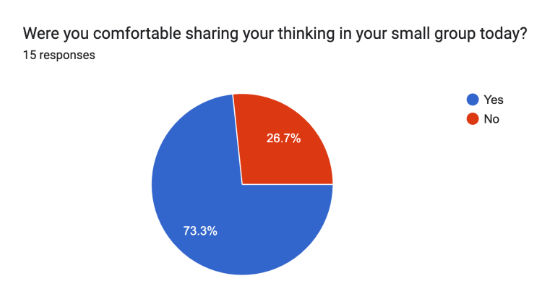

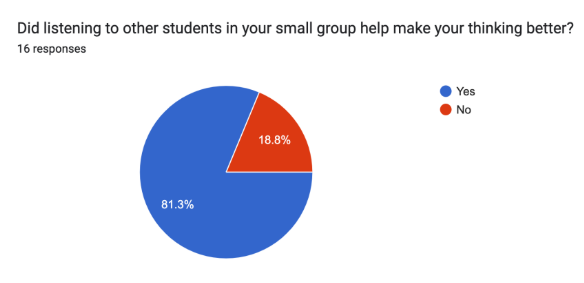

Many of the teachers in the program began using student sentiment data to sharpen their goals right away. One elementary school pair, for example, who entered the program intending to focus on the content of their lessons, collected baseline data and uncovered important insights that shifted their focus early in the school year. These teachers were surprised by some of the results, and shared their data with the community of coaching pairs. Here is a selection of the data that one of these teachers shared for discussion during a Community Meeting in the Fall of 2024:

This teacher shared that she did not realize her students were perceiving her as dominating whole class conversations, and that students also perceived a meaningful benefit in hearing from each other. She got more interested in her students’ experience of her classroom, and in her work with her coaching partner, she prioritized identifying teaching strategies to support students to hear from each other more often.

These data – and the insights and curiosity they stimulated – were presented during a Community Meeting, with other coaching pairs as the audience. By inviting teachers to share results from the practical measures with the community of coaching pairs in the program, we were able to promote a culture of both humility and professionalism at the same time. Practical measures made goal-setting a more informed process, helping teachers stay grounded in what matters most: the learning experience of their students.

Key learnings and impact on teachers

- Teachers’ sense of efficacy and professional autonomy

One of the most significant outcomes of the Reciprocal Coaching model was a notable boost in teachers’ willingness to try out new things. Teachers consistently shared that having structured time to reflect, test new strategies, and collaborate with peers made professional growth feel both possible and personal. One teacher described it like this: “It’s like weekly PD. And it holds me accountable. Before, I was like, ‘ok maybe next week, or next month… or next year,’ but now I’m doing it, I’m actually doing the things.” Instead of relying solely on top-down coaching, educators set their own instructional goals and used the Decision Tree to select teaching strategies to try. This ownership was indicated by another teacher who said “[The process is] “more intrinsic… it becomes about what I want to do, not what someone else is telling me to do.” The student sentiment data generated by the practical measures prompted teachers to experiment with teaching strategies that were responsive to the feedback they were getting from their students, and this combination of professional autonomy and the opportunity to analyze data from students about their experience in the classroom made their decision-making more agile and relevant to their own students.

- Data-informed decision-making

Practical measures were instrumental in shifting the culture of data use from compliance to insight. Teachers began to value student perspectives as meaningful data points, particularly when evaluating classroom culture and academic engagement. Surveys asking students to reflect on their sense of belonging, mathematical confidence, or experience with peer interaction helped teachers better understand the lived experiences of their students. The result was a stronger emphasis on designing classrooms that center student thinking and agency.

By embedding practical measures within the Reciprocal Coaching Decision Tree, teachers developed a clear, scaffolded process for goal-setting and instructional planning. This structure transformed the Decision Tree from a static reference into a dynamic tool that guided real-time data collection and reflection. Teachers used data —including student surveys, student work samples, and observational notes—to reflect on progress, iterate on strategies, and refine their teaching. As one participant explained, “The Decision Tree helped me realize I could try something new, track how it went, and adjust without waiting for someone else to validate the change.”

Ultimately, Reciprocal Coaching empowered teachers to blend professional judgment with actionable data, reinforcing the core belief that those closest to the classroom are best positioned to lead meaningful change.

Scaling and sustaining this work

“[The process is] more intrinsic… it becomes about what I want to do, not what someone else is telling me to do.” — Participating Middle School Teacher

Practical measures have proven to be a powerful lever for change—supporting teachers to have productive dialogue about student sentiment data in order to set more meaningful and appropriate goals and aligning their instructional shifts to real-time classroom experiences. Most instructional coaching programs rely on observation tools as key sources of data, and our Reciprocal Coaching program includes these as well. However, while observation tools shape adults’ gaze on students, the practical measures that we integrated into the program bring student experience – as reported by students – into the coaching process as data.

By rooting self-assessment in student voice, and by socializing the process of interpreting student data, the program aims to help teachers develop a deeper appraisal of their own practice. In contrast with common sources of school data that are often too distal and lagging to be useful to improve day-to-day practice (Bryk et al., 2015), practical measurement offers access to data that is timely and useful for informing instructional changes at the pace of everyday practice.

Beyond our current cohort, we see immense potential for practical measures to be adapted into other coaching models and district contexts. Whether through peer-based coaching or PLC structures, these tools can serve as actionable entry points for teachers to track student experience and learning, reflect on their teaching, and iterate in community. The lightweight, survey-based format makes them flexible and scalable, especially when paired with observation and planning protocols already in use across districts.

This work would not be possible without our partnership with WestEd. Their understanding of practical measures rooted in student experience has elevated the impact of our coaching work. By embedding the selected measures into our Decision Tree, we’ve supported teachers in making instructional choices that are directly informed by the voices of their learners. We are grateful for their thought partnership as we continue building a more reflective, student-centered professional learning ecosystem. We encourage other educators and coaching facilitators to explore the Math Practice Measures repository, and consider how they might enhance existing models of professional learning by catalyzing deeper reflection and focusing instructional improvement on what will make the most difference for students.

For more information on practical measurement, visit WestEd’s Repository of Math Practical Measures.

For more information about the Reciprocal Coaching pilot study, visit ConnectED’s Reciprocal Coaching Overview.

Big appreciation to all of the teachers in the 2024-25 Reciprocal Coaching program, and special thanks to teacher Laura Hopkins, who was willing to share her student data and experience.

The Reciprocal Coaching Pilot Study was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

)