Overview

What is the Instructional Framework?

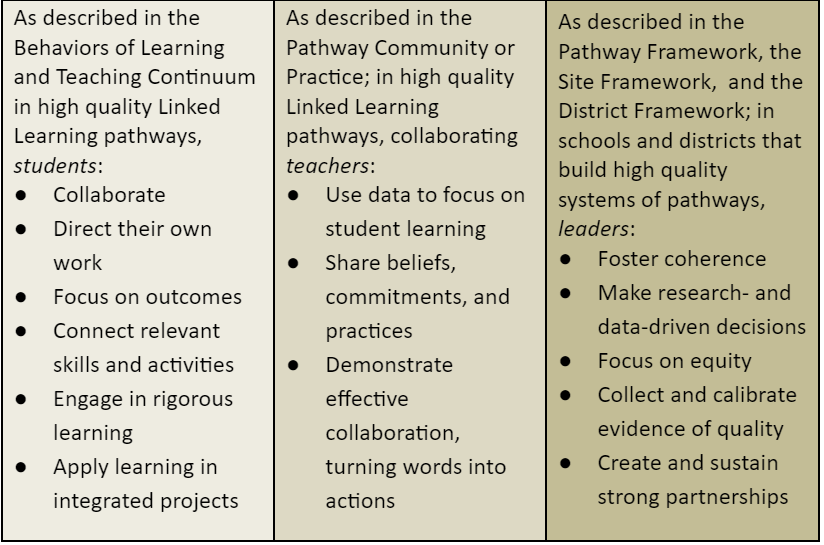

The Learning, Teaching and Leading Framework defines key characteristics of student and adult learning and teaching (and/or facilitation) practice within Linked Learning pathways. It illustrates how these actions and practices might be observed both inside and outside the classroom. The Framework includes two key documents:

- The Behaviors of Learning and Teaching Continuum describes the progress of students, teachers, and industry and community partners in developing the Linked Learning behaviors of learning and teaching (BLTs) that dramatically improve student motivation, empowerment, understanding and achievement.

- The Communities of Practice Continuum describe the progress of pathway teacher teams toward practices that produce high-quality, outcomes-aligned assessments and units of instruction, a collaborative and accountable pathway culture, equitable access, and high achievement for all students.

Purpose and Use of The Instructional Framework

The Instructional Framework’s primary purpose is to support Linked Learning teachers to achieve college and career readiness for all students through engaging, rigorous, and relevant learning that builds students’ sense of academic self-efficacy and taps their intrinsic motivation and interests.

The Instructional Framework…

- Supports pathway communities of practice to engage in dialogue about instruction and assessment and to guide the selection of practices for shared inquiry;

- Assists pathway and site leaders to foster shared instructional and assessment practices and norms that help create the pathway’s unique culture and outcomes-aligned assessment system;

- Guides pathway and site leaders, coaches, and district instructional staff in identifying and addressing teacher professional development needs; and

- Supports industry, postsecondary education, family, and other partners to understand and engage with learners and participate in the design and assessment processes.

The Instructional Improvement Toolkit clarifies the environments within which the characteristics, actions and practices described in the Learning, Teaching and Leading Framework are most likely to take root and flourish.

It may be that site and district learning environments are already set up in such a way that most students, teachers and leaders will find these skills and expectations easy to adopt.

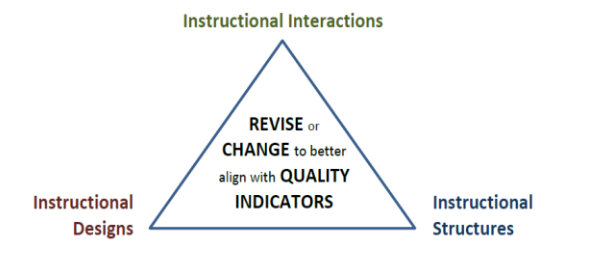

However, if learning environments are not yet set up in this way, pathway teachers, leaders, and support providers will need to shift existing instructional structures, instructional designs, and instructional interactions for widespread adoption of the Learning, Teaching and Leading Framework to become likely.

Resources:

- Behaviors of Learning and Teaching Continuum,

- Community of Practice Continuum (Pathway Community of Practice Continuum)

- Linked Learning Essential Elements for Pathway Quality, (Pathway Framework)

- Site Leader Toolkit (Site Framework)

- District Toolkit, (District Framework)

Despite nation-wide efforts to improve learning, teaching, and support practices in ways that significantly accelerate and deepen student understanding for all, especially those farthest from opportunity, we have yet to discover a “magic bullet” or universally applicable formula for success. We know that far too many classrooms look the same as they always have: bells ring every fifty minutes; teachers work individually behind closed doors, using curricula and consumables disconnected from the contexts in which students make meaning in their lives outside of school.

No educator–whether at the classroom, the school’s front office, or the district administration building–sets out to place limits on students’ learning. However, the supports, structures, plans, and relationships—the learning environment–that surrounds student and adult learners in our schools often undermine our improvement efforts by reproducing traditional status-quo patterns of achievement and failure, as well as by discouraging the risk-taking necessary for discovery-based inquiry and innovation. The biggest obstacle to improving learning and teaching may be the fact that we all went to school: it is hard to break free of the cultures and mental models that have shaped schools for so long.

Pathway teachers, leaders, and support providers can use the Instructional Improvement Toolkit to analyze current state, and take action to improve, classroom, school, and district environments by intervening in the instructional structures, designs, and interactions specific to their own role, as well as by influencing and supporting others in theirs.

This toolkit can be used to support two forms of instructional improvement:

IMPROVEMENT for QUALITY: involves a process in which individuals and teams use quality criteria and exemplars to clarify product and performance expectations, and to engage in a cycle of change and revision to improve products and performances, until they reach the desired level of quality.

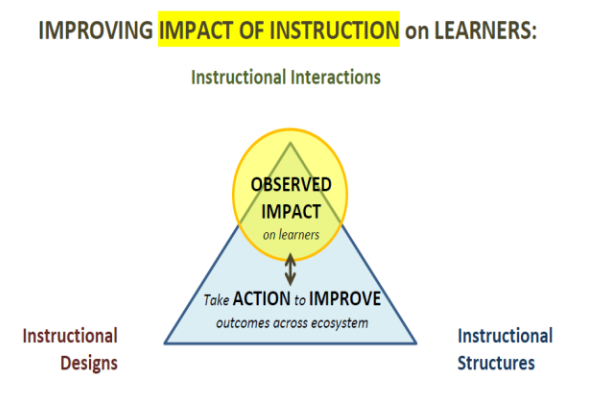

2. IMPROVEMENT for IMPACT: If you want to know whether a particular instructional decision or action has improved outcomes for learners, you have to observe what actually takes place when teachers and learners interact with designs, structures, and each other. A project plan might meet every quality outcome when designed, but if some students don’t trust others enough to share their ideas, for example, the lesson is unlikely to impact learning for those students.

Instructional Designs are plans, tools, and other artifacts made ahead of time, to describe the goals, outcomes, and intended trajectory of a learning experience (or set of experiences) a particular individual, group, or system intends to construct for its learners. When educators consider as much information about learners’ minds, needs, and experiences as can be understood, or at least imagined, before the learning experience actually takes place, learning becomes far more likely.

Quality instructional designs are necessary, but not sufficient, to ensure that learning actually takes place for all. To determine the impact of a particular design or plan, the designer and/or critical friends, teammates, and support providers will need to observe teachers and learners interacting with the design(s), analyzing observational data as well as products of learning to determine whether what was intended actually took place, for whom, and in what contexts or set of conditions.

Performance task, lesson, unit, and project plans are common examples of instructional designs, however instructional designs are not limited to classroom experiences. Work-based learning plans and teacher externship agendas are examples of instructional designs, as are professional development agendas, faculty meeting agendas, and strategic plans.

Instructional Design Examples also include:

- Mission and Vision Statements

- Programs of Study

- Student Learning Outcomes

- Curriculum-embedded tasks and activities

- Project Plans

- Professional Development Plans

- Site Plans

- Implementation and Improvement Plans

- District Accountability goals and plans

Improving the Quality of Instructional Design Resources:

- Pathway Outcomes

- Performance Assessments

- Integrated Projects

Improving the Impact of Instructional Design Resources:

- Why Examine Student Work?

- Student Work Analysis protocol (sample) and links to additional

- Low Inference Observations

Instructional Structures are the policies, resources, rules, and other systems that directly or indirectly impact the learning environment. While some instructional structures are within the direct control of teachers (such as setting up a classroom seating arrangement) many more are not (the school’s bell schedule, for example).

Improving instructional structures requires communication between leaders and those who experience the impact of their decisions; school, district, and policy decision-makers can’t determine which interventions resulted in improved impact for students (and which did not) without observing the impact of their decisions on others, and/or collecting feedback from those closest to classrooms and students.

(Add Graphic from original toolkit?)

While any structure could have an impact on the learning environment, certain structures consistently emerge as critical to the success of high quality college and career pathways:

- Common Planning Time for Pathway Teachers: Establishing common planning time for pathway teacher teams is a critical structure to support both student and adult learning cultures. Grade level teams are the most effective structure to promote the instructional shifts necessary for high quality pathways. Teachers accustomed to content area teams—especially those who have been team leaders–may struggle to collaborate in this new configuration.

- Cohort Scheduling of Pathway Students: A strong, successful pathway program ensures pathway students, regardless of their prior academic achievement, participate as a cohort in the academic and technical courses that are part of the program of study. The less “pure” a cohort, the more challenge pathway teachers will experience in their attempts to support students as a team.

- Curriculum Adoption and Guidance: What is “tight” and what is “loose” about your district’s adopted curriculum? Expectations about pacing, unit and skills sequencing, and district or school-wide assessments will have an impact on a pathway team’s ability to plan thematically integrated units and projects.

- Work-Based Learning Experiences: To what extent are work-based and work-aligned learning experiences considered part of the pathway learning culture—and to what extent are they experienced as “extra”? Without coherent connection between learning outcomes inside and outside the classroom, teachers can feel their time—and their loyalties—divided.

- Teacher Recruitment and Hiring: The best pathway teachers, leaders, and support providers are those who bring either experience in or a willingness to learn about interdisciplinary collaboration, career-themed integration, project- and problem-based learning, work-based learning, and authentic (performance-based and formative) assessment methods. District human resource policies and procedures, as well as site-specific autonomies, can make or break teams.

- Grading Policies: Competency-based and developmental approaches to evaluation and learning methods that encourage revision, collaboration, and demonstration of mastery—such as performance-based and authentic assessment, high quality peer and partner feedback, capstone and graduation projects, portfolios, and defenses of learning—facilitate the shifts necessary for successful Linked Learning college and career pathways environments. To what extent do school and district evaluation policies, mandated assessments, and data dashboards facilitate these approaches?

- Structures for Support and Intervention: A college and career readiness approach requires a commitment to structural equality through equal access, and gap-closing through personalized student supports. Effective student support requires both academic and non-academic attention for struggling students, using a strengths-based, developmental approach for positive youth development. While teachers are a crucial piece of the puzzle, they cannot do this work alone.

- Data Management: The structures above—especially common planning to support a cohort of students, curriculum expectations, grading policies, and structures for support and intervention, all require school and district capacity for data collection, management, and display. The more a data system is aligned to teacher assessment approaches and monitoring systems, the more use teachers will make of those data systems; and conversely, if district data systems are experienced as out of sync with what’s going on in classrooms, teachers and administrators are more likely to see data use as a compliance and accountability measure, or another thing added to an already full plate.

Improving the Quality of Instructional Structures Resources:

Improving the Impact of Instructional Structures Resources:

- Reciprocal instructional connections (district, site, pathway)

- Collecting Observational Data

Instructional Interactions are relationships, belief systems, and in-the-moment actions that facilitate or impede learning for groups and individuals.

Instructional interactions occur in interpersonal interactions that make or break an opportunity for learning. Both teacher/student interactions and peer-to-peer interactions have just as much power over a learning experience: for young students in classrooms as well as for adults learning in teams on the job.

It might seem like instructional interactions would be the easiest form of improvement, since these actions happen live (vs. in the future, as when we create instructional designs) and within our direct influence (vs. indirectly, as when we make decisions about instructional structures). However, we don’t always notice our own actions—especially in situations and relationships we experience as challenging—nor do we always find it easy to reason productively (vs. defensively) about our own experiences. For this reason, we often need a helpful, trusted observer—a teammate, leader, mentor, coach, or other “critical friend”—to help us discover gaps between our intentions and our actions, identify our existing strengths and goals, then plan to try something different next time. If a “critical friend” isn’t available, analyzing video or audio recordings are the next best thing.

Instructional Interaction Examples Include:

- Group Norms and Agreements

- Team Roles

- Activity Protocols

- Teaching and Facilitation Stances (“Warm Demander”)

- Status Intervention

- Growth Mindset

- Strength-Based Observations

Improving the Quality of Instructional Interactions Resources:

- The Behaviors of Learning and Teaching Continuum describes observable teaching and learning behaviors associated with high quality Linked Learning pathways.

- Norms, rule and roles help to clarify and model expectations for learners

We also recommend the research of our partners:

- Jobs for the Future Students at the Center Series: Motivation, Engagement, and Student Voice; Mind, Brain, and Education; Equal Opportunity for Deeper Learning

Improving the Impact of Instructional Interactions Resources:

- Strengths-based approaches to instructional interactions (video club)

- Psychological safety

- Producing Equal Status Interactions in Heterogeneous Groups

- The SCARF Model (for Teachers)

- The SCARF Model (for Leaders)

)